Deserere

DESERT, 2022

From the Latin desert or desertar

On April 18, 2004, a group of paramilitaries arrived with list in hand in Bahía Portete, Alta Guajira. They murdered and tortured six Wayuu women from the Fince Uriana, Fince Epinayu, Cuadrado Fince and Ballesteros Epinayu families: Margot Fince Epinayu (70 years old), Rosa Fince Uriana (46 years old), Diana (40 years old), and three girls Reina Fince Pushaina (13 years old), two Epinayu relatives (7 and 5 years old), who are still missing.

It was a massacre planned to dominate the port’s shipping lanes, coordinated by the paramilitary chief of the AUC’s Northern Block and military commander of the Wayuu Counterinsurgency Front Rodrigo Tovar Pupo, alias “Jorge 40” and Arnulfo Sánchez alias “Pablo”. Also participating in their execution was José María Barros Ipuana, known as “Chema Bala”, a Wayuu man and merchant from the port of Bahía Portete. These homicides had as additional consequences the displacement of 400 families who, very slowly and during these 18 years, have been returning to their completely devastated territory.

Source: The Bahia Portete Massacre. Wayuu Women in the Spotlight. Grupo de Memoria Histórica. 2010.

Each step revealed to me a time saturated by the manifest threat of a past that could repeat itself. Guided by Nazly Martínez of Eirruku Aapushana, Wayuu woman, I traveled to La Guajira followed by Jepirachi “the wind that does not disappear”, and that according to them “brings and carries orientations”; a wind that invited us to reach the traces, to know the violated places and to go through them carefully to understand their obscurity. I was also guided by children and young people and by the testimonies of Telemina Barros, Zoila Remedios Fince Epinayú, Rolan Fince Uriana, Mariana Epinayú and Maria Elena Fince Epinayú, elderly people and victims of the Bahía Portete massacre.

The contact with the Wayuu people allowed me to recognize them as strong and powerful, protectors of their place, clear in positions that respond to their tradition. They live among myths and symbols deposited in their natural geography and in their daily activities. The Wayuu woman sustains the rhythm of a matrilineal society, settles conflicts and leads the life of the community with an authenticity that stands out against the patriarchal structure of Colombian society. The Bahía Portete massacre – at the center of which are the bodies of tortured, murdered and disappeared Wayuu women – is a premeditated iteration of paramilitary violence, of its intention to penetrate the territory to break family ties, erase truths and impart fear.

It was inevitable to arrive with art, on the facts, to point them out and reveal their silence from that immense desert, from the drums, the ruins, the dream, the song, the cry and that echo of engines that violently and ferociously takes over the territory. The facts remain there, indelible; pain and distrust inhabit the place.

With the camera I follow a Wayuu boy and his donkey who, despite staying protected by the daily calm of their own work, have to live closely the irruption of trucks that cross the desert at full speed. In the atmosphere one can feel the gestures of the paramilitaries that have roamed the region for years and in every corner to exercise with their violence the inclement “ownership” that still remains.

It was necessary to approach to confront the resonances, which still subsist in the wounds of a violated territory; to the pierced, abandoned and forgotten space of the desert, to feel there also the recondite and powerful vibrations of a community, a world and a present that resists.

Understanding the rhythms of this territory has been complex; its presence is installed and at the same time escapes me. I immersed myself in it by the hand of literary sources-Weildler Guerra Curvelo, María Emma Wills and María Luisa Moreno-to try to understand it, and to propose ways of perceiving. With Camilo Echeverri and Daniel Cuervo on camera, we made a journey along untraced paths, we suffered strong and dusty temperatures to find the images immersed in the desert. With Paloma Valencia in the production assistance, with the compass in the driver José Diaz Pana of Eirruku Epieyu at the margin of time and with the microphones as witnesses of Juan Forero and Cristian Prieto, we tried to capture the density of a sound that vibrates the agitated heat of the wind. In its intensity, the stories, the silences and the textures of a space whose extension exceeds us and only in this way allows us to begin to feel its powers.

Clemencia Echeverri

Stills de la obra

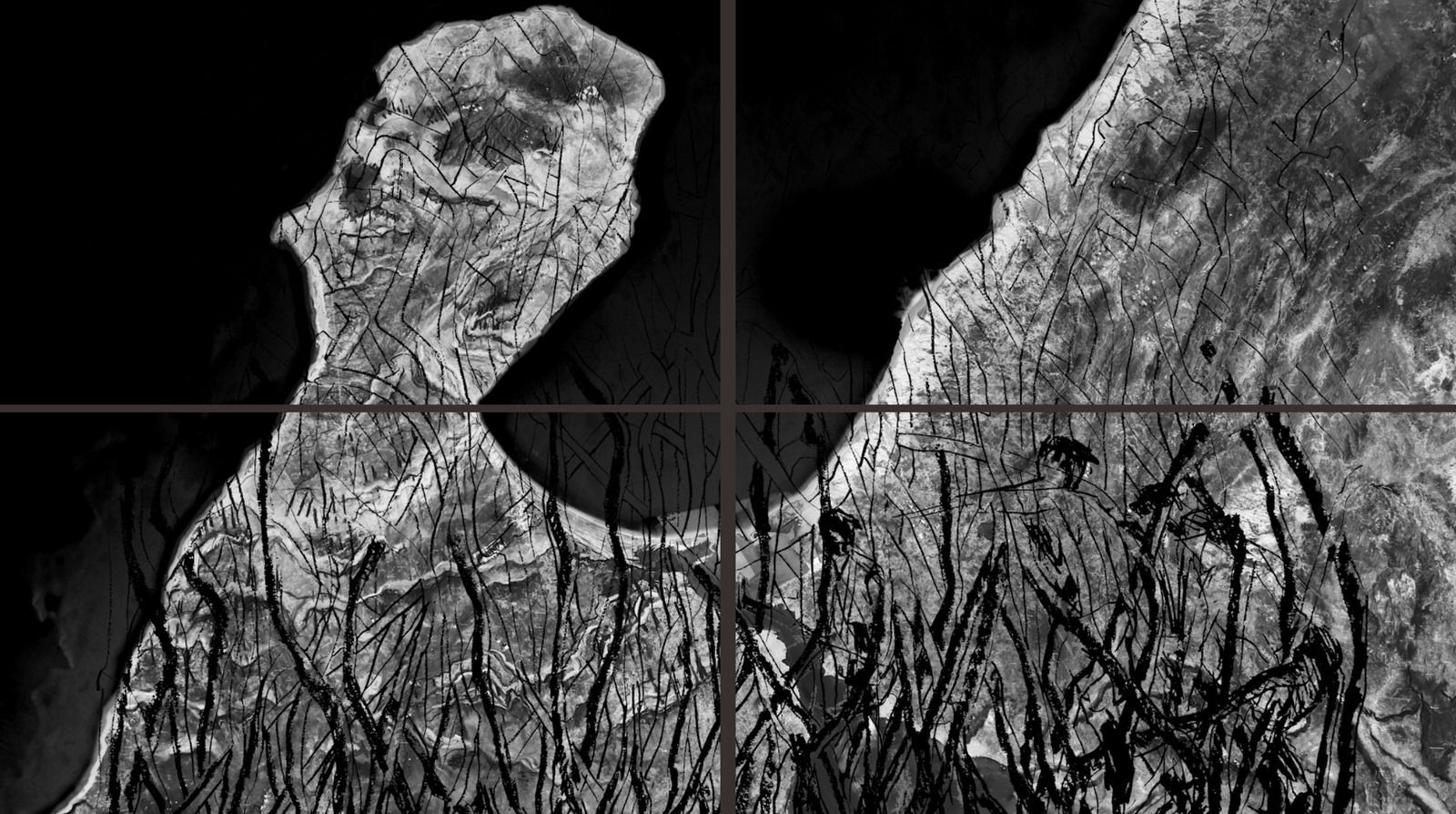

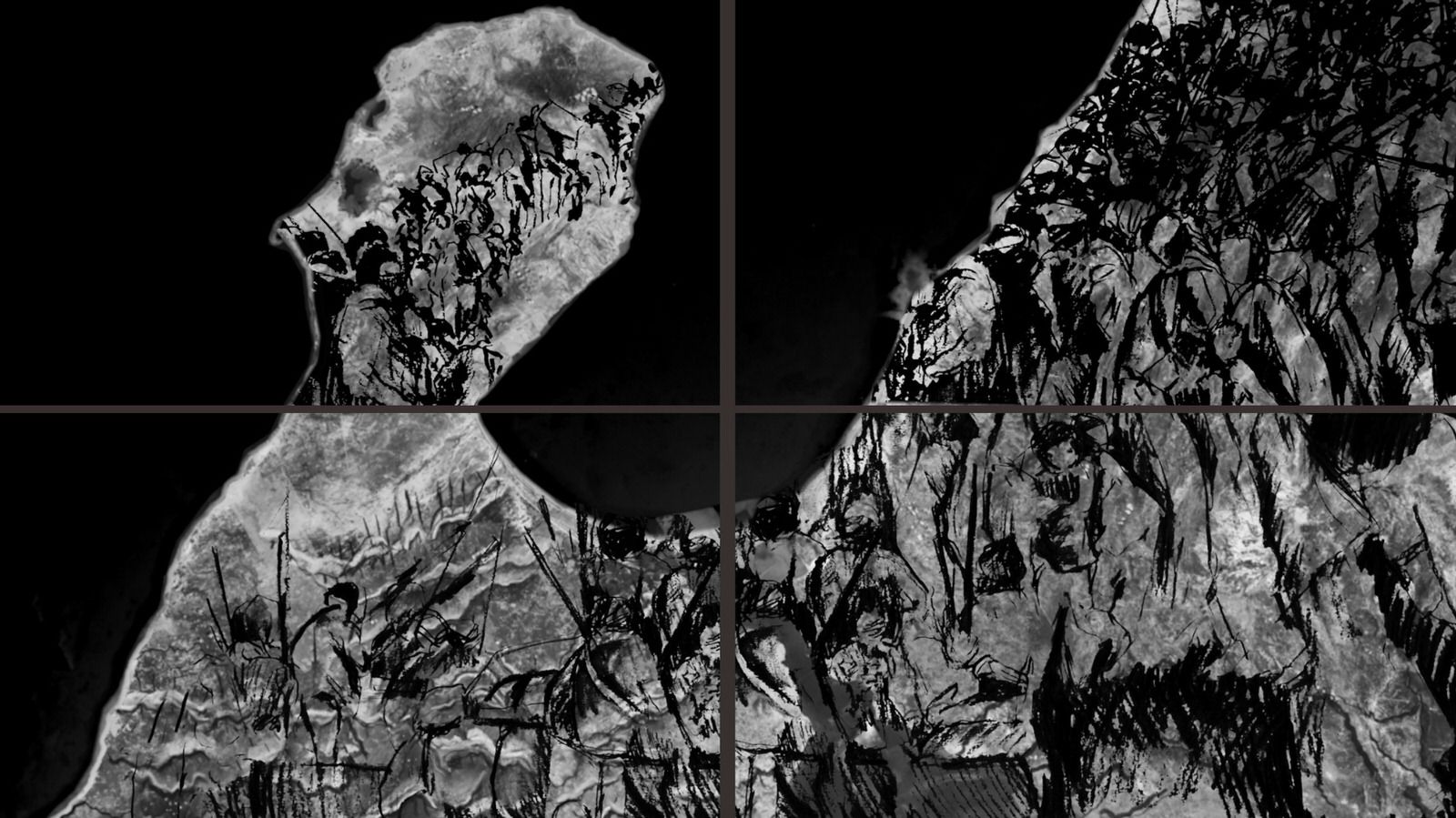

Deserere – Trupillo

Frame by frame animation in drawing for videowall on 4 monitors, it makes counterpoint to the installation that traces and looks for that violated path on the map.

Still de la animación.

Still de la animación.

Still de la animación.

The memory of jepirachi

Outushii wayaa ma’akaa katuule wouu .

(We die as if we were still alive).

Vito Apüshana

“The geographical and cultural space of the La Guajira desert, which expands between the confronting projections and the texture of its soundscapes, is one that we enter without ever fully entering: it both invades us and prevents us from accessing it.

In the desert that this video installation by Clemencia Echeverri presents and evokes (the desert is not only what we see but also the gallery through which we walk aimlessly), everything is fragment, glimpse, secret: each instance of the journey through the interconnected rooms-each shot and each detail, each sound and each echo-is an entrance to the immensity of the Wayuu world whose presence, however, interrupts all promise of access.

As suggested by the Latin root that gives the work its title, the desert is here, then, a place that cannot be located with certainty in the space and time of the known and the proper, that remains always out of field and thus mocks the presumed power of the gaze: the place of an abandoned, deserted, forgotten world, but also a world that evades the force of oblivion with its own forms of remembrance.

The work resists the hierarchies that hegemonically govern the regime of the sensible by presenting the resistance of that world in action: the desert abandons, forgets, deserts the image that exposes it in its flight. The space that expands between the visual and sound trajectories of Deserere places us, by dislocating us, in the extension of a territory whose radical opening responds to only one will: the will of the wind. It is no coincidence that it is precisely the tenuous and powerful force of the wind of the Alta Guajira that travels through, and thus ties with its movement and vibration, each and every one of the visual and sound images that unfold as we walk without destination through the video installation.

Deserere wonders and asks us how to get in tune with the form of memory, as ancestral as it is future, that survives and breathes in this desert wind; how to listen to its claims for justice, how to accompany the call of the dead that travel in its wake towards Jepira, honoring the distance between one world and another.

How to inhabit the space of that difference; how to accompany it, witness it, listen to it in its obstinate call without translating what it evokes; how to remember-that is, how to feel: how to bring back (re) to the heart (cordis)-the memory of the unburied bodies that still await their second burial so that, as Apüshana’s verse says, they can finally die as if they were still alive? “.

Text of the catalog

María del Rosario Acosta and Juan Diego Pérez,

philosophers and art theorists.

Installation at Espacio Continuo Gallery. Bogotá, 2022.

Behind the scenes. La Guajira, Colombia.

PRENSA

• Clemencia Echeverri: el arte de recuperar el dolor enterrado. Periódico El Espectador.

• Clemencia Echeverri, imágenes contra el olvido. Revista Cambio.

• La memoria de Jepirachi. Revista de arte contemporáneo – Artishock.

• Deserere y el videoarte como denuncia. Razón Pública.

• Obra de Clemencia Echeverri muestra las secuelas de la violencia en Bahía Portete. W Radio.

• “En Colombia hemos convivido con la violencia”: Clemencia Echeverri. Periódico El Tiempo.

• Clemencia Echeverri y los wayús. Periódico El tiempo.

CREDITS

Director: Clemencia Echeverri

Camera: Camilo Echeverri and Daniel Cuervo

Camera assistant: Carlos Arbeláez

Video editing: Victor Garcés

Sound and sound design: Juan Forero

Sound assistant: Cristian Prieto A

Production: Nasly Martínez and Paloma Flórez

Animation editing: Mariana emilia vejarano